Read this blog post in: Português | ગુજરાતી

As one would walk down the streets of Diu, hearing the rhythmic beats of handloom pedals as the artisans wove their traditional creations was unavoidable. Diu served as a home to the craft of making handwoven fabrics. It was fascinating to see how bundles of simple, raw and colourless cotton threads resulted in rich, elegant and colourful fabrics, such as saris, panetars, dhotis, towels and rugs.

The town is divided into different communities for whom the weavers contributed their work, in return for monetary incentives which formed a major contribution to their income. The families were small scale firms that came from a line of weavers and they distributed the fabrics to potential buyers. The raw cotton threads were spun and dyed. Once they arrived at the weavers’, the yarn was prepared after which it was set to the loom. Each filament was fixed to the yarn by twisting in a certain manner. Generally done by the men folk of the community, the sari and other fabrics were then woven and packed neatly to be delivered to the buyer.

The Vanzas are part of the social fabric of Diu and traditionally worked as weavers. The weaving of saris, panetars, dhotis, towels, rugs and other fabrics was their main activity. These were bought by the banianes who in turn sold them in Africa.

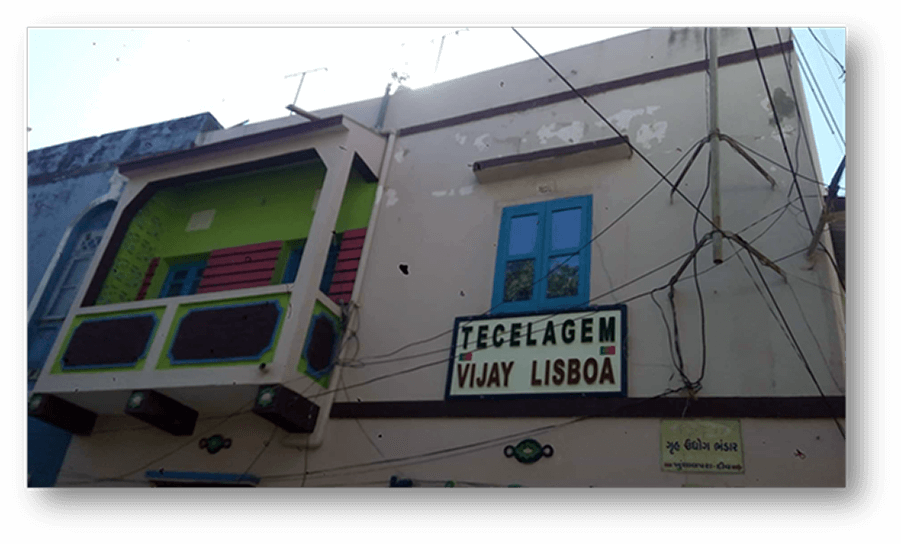

At a crossroads in the Koliwada, near the Travessa Cuxalpara, a recently painted building displays a big sign with the words ‘Tecelagem Vijay Lisboa’ (Vijay Lisboa Weaving) with two small Portuguese flags on either side.

A big signboard displayed on a building with the words “Tecelagem Vijay Lisboa”. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

The family home of Shri Aracchande Panachand, where on the first floor, his grandson, Shree Vijay Cumaldas, maintains the inherited family skills of weaving. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

Vijay is the last weaver of Diu, and so the last representative of the weaving knowledge of the Vanza community. He spends half of his day weaving wedding saris in tones of red and gold for the Kharwa fishing community. The long history of Diu’s weaving has a witness, maintaining the inherited family skills on the first floor of a modest house in the old town.

Vijay’s paternal grandfather, Shri Aracchande Panachand, born in Diu in 1908, and his father Shri Cumaldas Aracchande, born in Diu in 1936, transferred the skill of weaving from one generation to another. Vijay’s main activity is that of a civil constructor, and part of the buildings and houses he builds are also sold to members of his community who live in Maxixe, a Mozambican city facing the coastal city of Inhambane, in the south of the country. He also lets out properties to visiting customers and guests from the community. He is the owner of a small restaurant called Khana Sutra located on Ghodiya Street opposite Pranami temple.

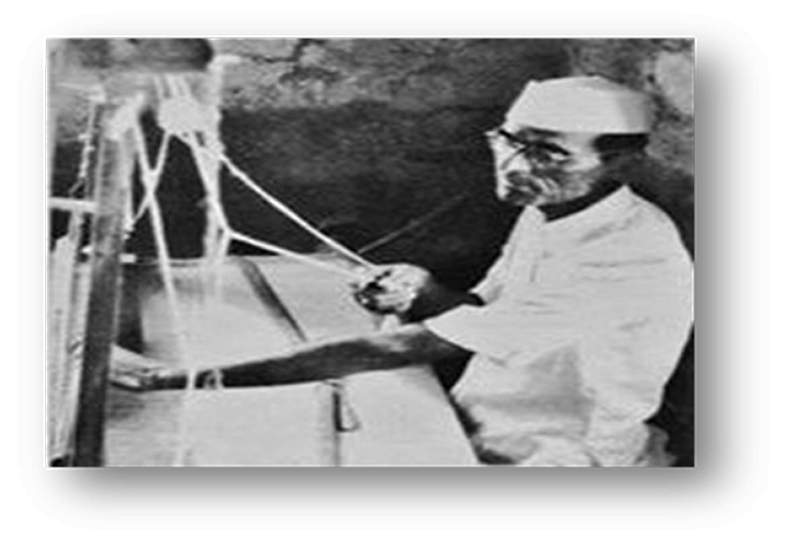

The weaver, Shree Aracchande Panachand, in Diu. Photo courtesy Mr. Orlando Ribeiro.

The photo story aims to capture the very essence of the weaver, Vijay Cumaldas and his pride in carrying the art until now. The art sees no gender or age as everyone equally contributes to the making of the sari. The artisan talks with glee on his face and shine in his eyes, as he explains his work and tradition in great detail. He has sheer determination to keep burning the heritage and practice of weaving. The family members of the weaver are as closely knit as the warp and weft of their creations.

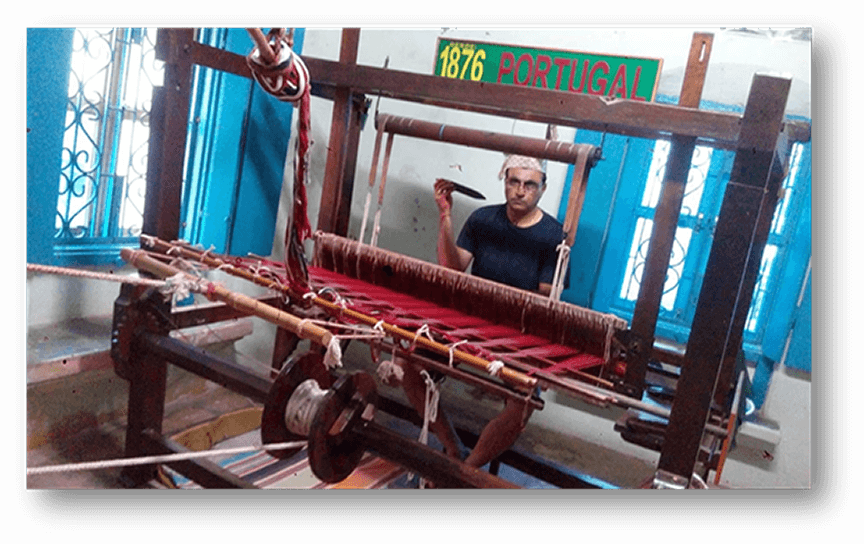

Shree Vijay Cumaldas keeping the tradition alive. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

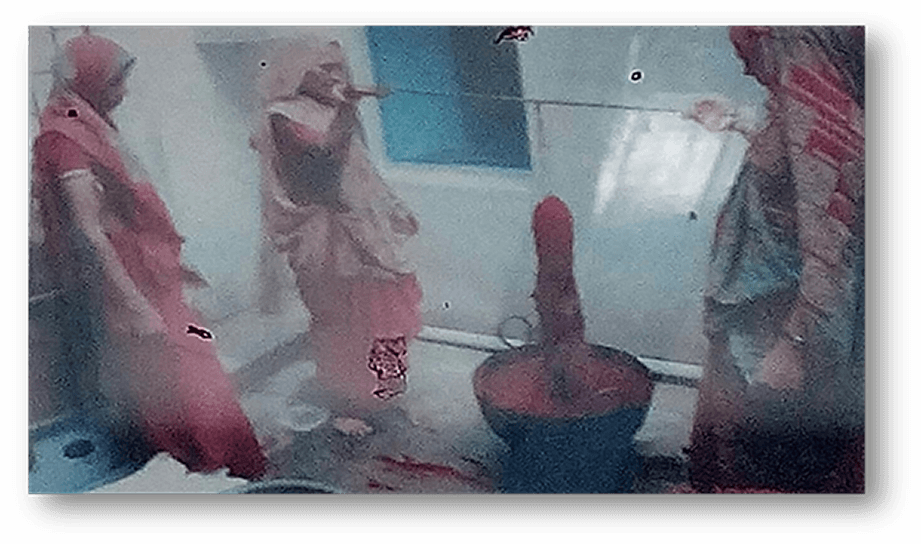

The pre-weaving process: Dyeing – During the process of dyeing, colours are added to the threads. The workers are seen dyeing the yarns. The workers soak the yarns in water before dyeing it. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

The pre-weaving process: Dyeing – During the process of dyeing, the weaver adds colours to the threads. The workers are seen dyeing the yarns. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

The pre-weaving process: Dyeing – During the process of dyeing, the weaver adds colours to the threads. Bhavnaben Cumaldas, with the aid of workers, is seen dyeing the yarns. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

The pre-weaving process: Drying – Dyed yarns are kept for drying under the sun. The dyed yarns are seen hung for drying under the sun. Vijay’s elder son, Grishal, is proudly posing for the photograph. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

Bundles of yarn, also known as hanks. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

The pre-weaving process: Soaking of yarn – Yarn is soaked in water before it is dyed. The workers are seen soaking the yarn in water before dyeing it. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

The pre-weaving process: Stretching of yarn – Yarn is laid stretched for rolling on warp beams. In this photograph, one can see the yarn stretched between two poles. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

The pre-weaving process: Spinning – Cotton yarn is spun using a charkha, a hand-operated spinning wheel. The spun cotton yarn is braided into skeins. Some of the skeins are loaded onto bobbins. These will be used for the weft, the crosswise threads of the cloth. Others will be used for the warp, the lengthwise threads of the cloth. Grishal is seen winding the yarn onto bobbins. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

The pre-weaving process: Preparation of warp – The threads from the bobbins behind the reed are taken through the reed to the warping frame. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

The pre-weaving process: Preparation of warp – Once the yarn dries, it is separated and spaced with the aid of a small, handheld reed on a wall-mounted warp frame. Bhavnaben Cumaldas prepares the warp of the sari for the loom. She is seen with the reed, separating and spacing the warp thread. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

The warp thread mounted on the loom. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

A beautiful piece of sari draped on a mannequin. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

Hank yarn for the weft is wound onto a pirn, which is a small bobbin. The weft yarn is then inserted into a shuttle. Weft preparation is done on the charka, using the fingertips to give the correct tension to the yarn. The shuttle is a device used in weaving to carry the weft thread back and forth between the warp threads. Photo courtesy Shree Vijay Cumaldas.

The Vanza community was able to read the economic opportunities that Mozambique could offer and was very much aware of the development of long-established Goan and Gujarati communities in that Portuguese colony. Banyan families had been extremely active in the trade with Mozambique for the last two centuries and, at the turn of the twentieth century, with the local economy in accentuated decline due to the demise of the textile trade, the Vanza, traditionally weavers, and the Darji, who worked as tailors, looked for work in a Mozambique that promised new prospects. It is revealing that two communities directly connected with the textile production would migrate when this trade faded away from their homeland.

Indian Weavers: The Poem

Sarojini Naidu, with her observant eye and understanding heart, has explored the Indian philosophy of life and death, darkness and light, and happiness and misery in her song ‘Indian Weavers’. Weaving was a very important folk vocation in India at the time of Sarojini Naidu. Mahatma Gandhi respected this profession with his head and heart. He used to weave his own clothes. He laid stress that all Indians should wear garments which are hand woven. Kabir Das, the greatest sage and saint of India, was a weaver by his profession.

Even today, weaving is one of the most important folk vocations in the remote villages of India and the weavers are the most important folk characters. Sarojini’s poem “Indian weavers” introduces a typical Indian scene, that of weavers particularly from a rural area, weaving clothes of different colours on handlooms. The first two lines of each stanza form a question and the last two lines form the answer. The three questions are asked at different times of day, each representing different stages of life. One at the break of day, when nature awakes and new life emerges, the other at nightfall, when a couple eagerly awaits marriage, and the last during the moonlight chill, in which the very sound of the epithet ‘chill’ is associated with the cold stillness approaching death.

Indian weavers

Weavers, weaving at break of day, Why do you weave a garment so gay?

Blue as the wing of a halcyon wild, We weave the robes of a new-born child.

Weavers, weaving at fall of night, Why do you weave a garment so bright?

Like the plumes of a peacock, purple and green, We weave the marriage-veils of a queen.

Weavers, weaving solemn and still, What do you weave in the moonlight chill?

White as a feather and white as a cloud, We weave a dead man's funeral shroud.

Sarojini Naidu

Here, Sarojini has assembled several elements to weave the complex texture of the poem, including birds, colours, different hours of the day, different moods, similes and sound patterns, each emerging into the other. They behave harmoniously to portray the Indian philosophy of human life, for example, the first stanza sets the scene during the break of day and talks about the blue-winged halcyon bird, which goes well with the phenomenon of a child taking birth. The break of day implies the sudden emergence of something and the halcyon bird is a symbol of the spirit and the beginning of creation, and the sea is the chaos which the halcyon charms into the cosmos for the purpose of breeding. These two symbols suggest birth and creation.

The gay robes, embodying the gaiety of nature’s heart towards newly born life, the peacock with its purple and green plumes (feathers), and the nightfall (suggesting the hour of expectancy), all resemble an Indian girl’s wedding dress and marriage time, symbolising life’s colours and splendour as in India the marriage ceremonies are often held at night. In the final stanza, Sarojini depicts a white feather, which is neither the wing nor plume of a living bird, but is a feather torn off of a dead bird. The weavers weaving in solemnity produce a funeral shroud. The white feather, chill moonlight and solemnity all symbolise the dark atmosphere of death.

Hence, Sarojini’s poem ‘Indian weavers’ is symbolic or allegorical since it is only a thought rather than an experience. The whole comedy and tragedy of human life based on Indian philosophy is brought out here. The three Fates (here the weavers) are weaving the mingled web (texture) of human life. Belief in the Fates is almost a universal phenomenon. The Fates in Indian mythology are embodied in the concept of Brahma, Vishnu and Rudra. Brahma is known as the god of creation, who is usually depicted sitting on a lotus coming out of the blue sea, which is presented in the first stanza by recalling the blue of the halcyon’s wing.

Vishnu is the god of prosperity, marriage, wealth and splendour, corresponding with the splendour of a peacock’s plumes in the second stanza. Lastly, Rudra, the god of destruction and death is represented by the white of the feather and moonlight chill in the third stanza. Each of the three are engaged in their respective tasks, weaving the ‘robes of a new-born child’, ‘marriage veils’ and a ‘funeral shroud’.

So, a man’s birth, life and death are the subject matter of the ‘Indian Weavers’ and the poem is the symbolic representation of the Hindu Trinity of Brahma, Vishnu and Rudra based on Indian philosophy. The transience of human life implied in the three stanzas does not fail to move our hearts. Sarojini has also skilfully retained the simplicity and uplifting music of an Indian folk song. The lyrics have a symbolic significance, in regard to the deep Indian philosophy of life, birth and death, hidden in the rich texture of the poem, providing layers within layers of meaning.

Tribal hand painted art on handloom weave

Beautiful Patachitra Painting on Sari

Madeleine (Sandra Kerr) and Gabriel (John Faulkner) sang the Weaving Song in the tenth episode of the 1974 children's TV series Bagpuss, The Old Man's Beard, and on the 1998 Smallfolk CD Bagpuss: The Songs & Music, followed by the tune The Laird of Drumblair.

Stick in the Wheel sang the Weaving Song in 2018 on their CD Follow Them True.

Madeleine and Gabriel sing the Weaving Song

Bagpuss - The Songs & Music

I’m a weaver, a master weaver, I’ve got a loom where the best cloth's made. Plain cloth, twill, brocade or satin, I’m the master of my trade. Shed the warp and swing the shuttle, Beat the reed, the weft is laid.

I can wind a flying bobbin, I can warp a theme of thread. I can weave a sheet of linen, Fit to grace a royal bed. Lift the heel and fly the shuttle, Swing the reed, the weft is laid.

Hear the din of loom and shuttle, Weaving is a noisy trade. See how even, soft and gentle, Lies the cloth when it is made, Lies the cloth when it is made.

Stick in the Wheel sing the Weaving song

Stick in the Wheel - Follow Them True

I’m a weaver, a master weaver, I’ve got a loom where the best cloth's made. Plain cloth, twill, brocade or satin, I’m the master of my trade. Shed the warp and swing the shuttle, Beat the reed, the weft is laid.

I can wind a flying bobbin, I can warp a theme of thread. I can weave a sheet of linen, Fit to grace a royal bed. Lift the heel and fly the shuttle, Swing the reed, the weft is laid.

Hear the din of loom and shuttle, Weaving is a noisy trade. See how even, soft and gentle, Lies the cloth when it is made, Lies the cloth when it is made.

Post by Dipac Canacsinh

Acknowledgements

It is my radiant sentiment to place on record my deepest sense of gratitude to my cousin, Mr. Pradip Vassantlal for his assistance in the editing and proofreading of the Gujarati version of this article.

A special thanks to Mr. Vijay Kumaldas for providing me with the photographs used in this article.

I also thank the President of Diu Vanza Darji Samaj UK, Mr. Paresh Amarchande, for providing me with the photograph of his visit to the weaving workshop at Mr. Vijay Kumaldas' residence, taken during his visit to Diu in February of 2018.

Mr. Paresh Amarchande at the weaving workshop at Mr. Vijay Kumaldas' residence during his visit to Diu in 2018. Photo courtesy Shree Paresh Amarchande.

Listen to the songs related to weaving in the audio player below.